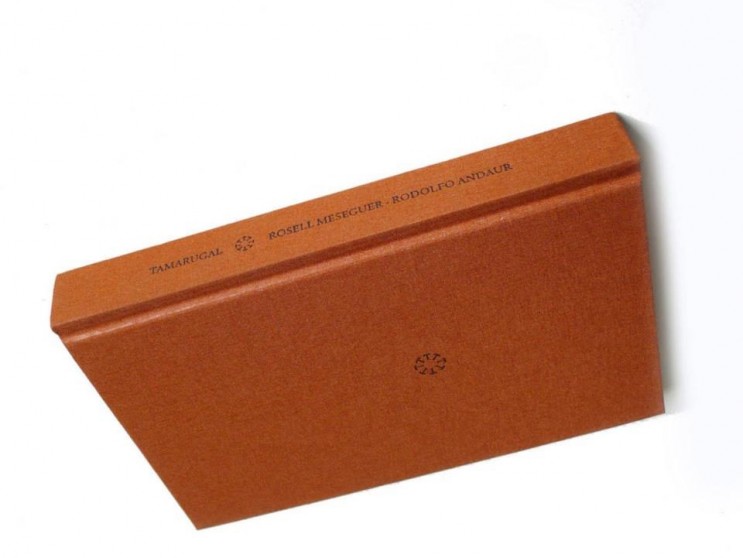

The fascination for exploring and watching desertic places makes us reflect on their unique landscapes. This time, we will go into the remote Atacama Desert landscapes and the Chilean-Bolivian altiplano.

Places with a geography dominated by swirling dust storms during the day, and where a starry sky at night gives us great uneasiness. But the peculiarity of this land is the relationship between its politic and territorial guidelines, an issue that has modeled its distinctive aspects. Aspects which, indeed, show the boundaries through its traces and indelible marks.

Dusty documents, newspapers, and photographs, as well as corrugated iron, glass and Oregon pine, make up a memorial for what once were villages and ranches built in this place. That is why oral tradition that has spread the knowledge about these solitary quarters in the plains, the altiplano, and even some lush canyons, tend to intensify that withered vastness. Nevertheless, the regions that are part of the Atacama Desert in Chile (Arica and Parinacota, Tarapacá, Antofagasta and Atacama) do not show such devastation and immense uniformity of the surrounding landscape anymore. And this happens because this territory has faced massive human actions that have transformed its space continuously, from sea to mountain.

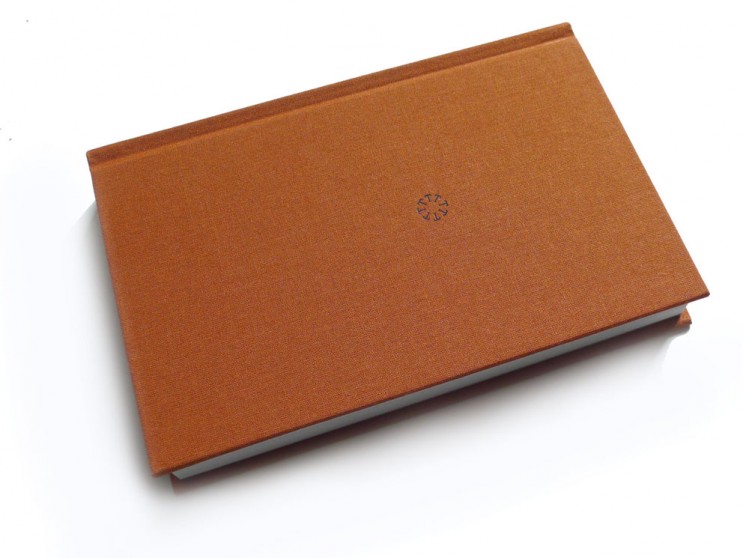

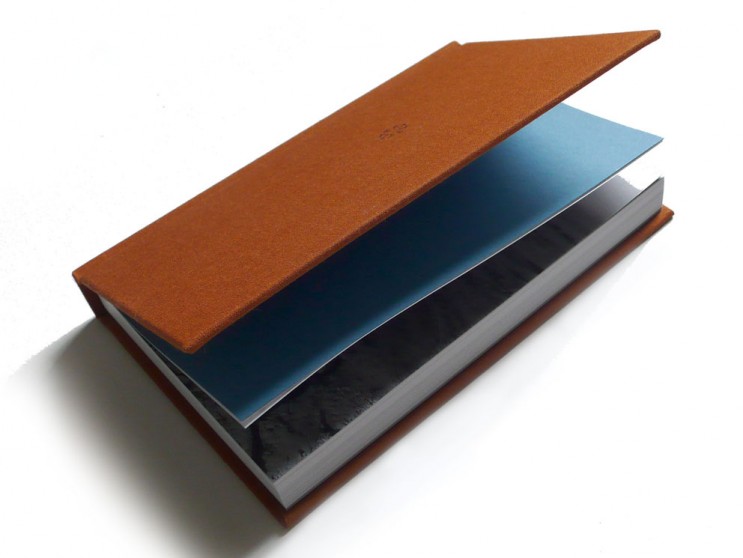

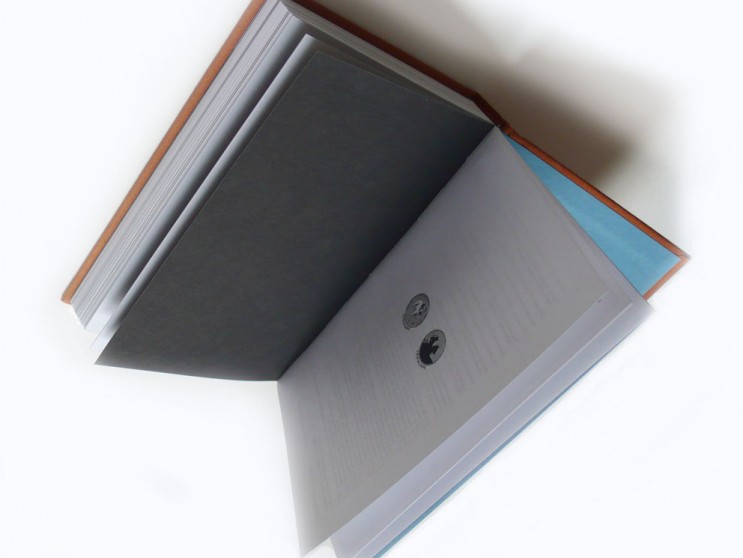

Thus, these “unearthed” stories are the ones that have confirmed the structure of the desert, its unsustainable population mobility, a hazardous mining development and the tireless struggle for understanding the homeland. Because its functionality becomes the foundation for proposals that beyond the exhibition of landscapes, express a political and aesthetic discourse which bursts in the wanderings of artists like Rosell Meseguer. An artist who not only reveals the traces of socio-economic phenomena related to the mining labor through images, but who also questions the tangible and intangible treats of a territory ruled by massive dunes, narrow valleys and thousands of tamarugo trees.